Today, medical school enrollment is nearly equivalent between men and women across the country – but most women physicians still believe that disparities exist between male and female doctors due to personal experience and staggering gender differences in medical leadership. While 73 percent of health service and medical manager jobs are held by women, only 18% of hospitals CEOs and 4% of healthcare company CEOs are women. Among division chiefs, medical school deans, department chairs, and hospital CEOs, only 20 percent are women. We have a long way to go, but women throughout history fought to be able to stand alongside men as practicing physicians, and the leaders of these changes deserve recognition.

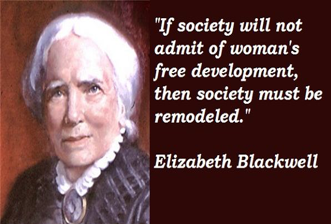

In the U.S., all physicians were men until 1849 when Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first American female doctor. The fact that she was allowed into medical school was only due to the fact that her male peers at Geneva Medical in western New York believed her application to be a joke. After having been being rejected from several medical schools, the dean at Geneva put her application to a vote among the male students. A single “no” vote would be cause for rejection. None voted no, thinking it was not a serious question. Blackwell faced many obstacles in her career – she was asked to leave operations because of her gender, and was not allowed to attend lectures on reproductive anatomy – but persevered and became a courageous leader for women in medicine. In fact, perhaps inspired by her leadership, Blackwell’s younger sister became the third woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree.

In the U.S., all physicians were men until 1849 when Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first American female doctor. The fact that she was allowed into medical school was only due to the fact that her male peers at Geneva Medical in western New York believed her application to be a joke. After having been being rejected from several medical schools, the dean at Geneva put her application to a vote among the male students. A single “no” vote would be cause for rejection. None voted no, thinking it was not a serious question. Blackwell faced many obstacles in her career – she was asked to leave operations because of her gender, and was not allowed to attend lectures on reproductive anatomy – but persevered and became a courageous leader for women in medicine. In fact, perhaps inspired by her leadership, Blackwell’s younger sister became the third woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree.

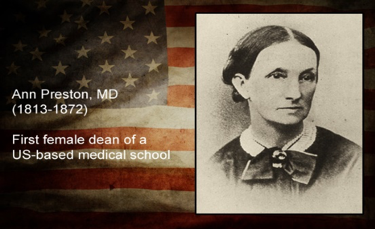

Dr. Ann Preston was another woman rejected from admission to four medical schools because of her gender, and finally was accepted into a new school, the Female Medical College of Philadelphia, in 1850. During her time there, the Board of Censors of the Philadelphia Medical Society prohibited women from public teaching facilities in its jurisdiction which meant many female medical students were lacking very important clinical experience. Three years after her acceptance, Dr. Preston became a professor of physiology and hygiene and began fundraising efforts for a Women’s Hospital, which opened in 1861. At this facility, she developed a training program for nurses and became the first women dean of the college. In 1868, after years of her fearless advocacy, the barriers were broken down and women were allowed into the general teaching clinics in Philadelphia.

Dr. Ann Preston was another woman rejected from admission to four medical schools because of her gender, and finally was accepted into a new school, the Female Medical College of Philadelphia, in 1850. During her time there, the Board of Censors of the Philadelphia Medical Society prohibited women from public teaching facilities in its jurisdiction which meant many female medical students were lacking very important clinical experience. Three years after her acceptance, Dr. Preston became a professor of physiology and hygiene and began fundraising efforts for a Women’s Hospital, which opened in 1861. At this facility, she developed a training program for nurses and became the first women dean of the college. In 1868, after years of her fearless advocacy, the barriers were broken down and women were allowed into the general teaching clinics in Philadelphia.

While Dr. Preston was busy reshaping the landscape of medicine in Philadelphia, other women were breaking new ground elsewhere. In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first female African-American doctor in the U.S., after graduating from the New England Female Medical College in Boston – a school which was mocked by many male physicians who claimed that women lacked the strength for completing a medical curriculum and many medical subjects were not suited to their “sensitive and delicate nature.” To give credence to this remarkable achievement, it should be noted that there were only 300 women out of 54,543 physicians in the U.S., none of whom, aside from Dr. Crumpler, were African-American. Dr. Crumpler dedicated her work to women and children, especially freed slaves. She published the book “A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts,” one of the first medical books written by an African-American author.

While Dr. Preston was busy reshaping the landscape of medicine in Philadelphia, other women were breaking new ground elsewhere. In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first female African-American doctor in the U.S., after graduating from the New England Female Medical College in Boston – a school which was mocked by many male physicians who claimed that women lacked the strength for completing a medical curriculum and many medical subjects were not suited to their “sensitive and delicate nature.” To give credence to this remarkable achievement, it should be noted that there were only 300 women out of 54,543 physicians in the U.S., none of whom, aside from Dr. Crumpler, were African-American. Dr. Crumpler dedicated her work to women and children, especially freed slaves. She published the book “A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts,” one of the first medical books written by an African-American author.

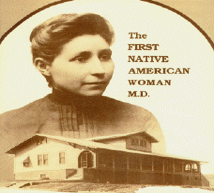

Women continued to make strides throughout the nineteenth century. In 1889, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte became the first American Indian woman to graduate from medical school. As she told it, she decided to become a doctor when she saw a white physician refuse to give medical care to a sick Indian woman, who then died. She graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and returned to Nebraska where she served both Indian and non-Indian patients. Interestingly, she also became the first person to receive federal aid for education.

Women continued to make strides throughout the nineteenth century. In 1889, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte became the first American Indian woman to graduate from medical school. As she told it, she decided to become a doctor when she saw a white physician refuse to give medical care to a sick Indian woman, who then died. She graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and returned to Nebraska where she served both Indian and non-Indian patients. Interestingly, she also became the first person to receive federal aid for education.

As more women entered medicine, they began bringing radically different ideas to the table, reshaping many of the types of treatments that female patients could receive. Women of our present day can thank a physician from the turn of the century who was considered a rebel during her time, Dr. Marie Equi, for reproductive choices. After working in a textile mill from the ages of 8 to 13, she graduated from medical school in 1903. In the course of her work, she fought hard for women’s rights that most of us would now consider fundamental: she devoted much of her career to expanding women’s options for reproductive health, including access to contraception and abortion.

As more women entered medicine, they began bringing radically different ideas to the table, reshaping many of the types of treatments that female patients could receive. Women of our present day can thank a physician from the turn of the century who was considered a rebel during her time, Dr. Marie Equi, for reproductive choices. After working in a textile mill from the ages of 8 to 13, she graduated from medical school in 1903. In the course of her work, she fought hard for women’s rights that most of us would now consider fundamental: she devoted much of her career to expanding women’s options for reproductive health, including access to contraception and abortion.

Dr. Sara Joseph Baker was a well-known warrior in public health, especially among immigrants in New York City. In 1917, she claimed that more babies in the U.S. were dying than soldiers in World War I. She became an ardent advocate for children’s health rights and spoke about the damage poverty and ignorance was causing them, and is perhaps most famous for being the doctor who tracked down “Typhoid Mary.” In her memoirs, “Fighting for Life,” she reflected on the realization that preventative care was as powerful as new treatments and cures to many people, remarking, “the way to keep people from dying from disease, it struck me suddenly, was to keep them from falling ill. Healthy people don’t die. It sounds like a completely witless remark, but at that time it was a startling idea. Preventative medicine had hardly been born yet and had no promotion in public health work.”

Dr. Sara Joseph Baker was a well-known warrior in public health, especially among immigrants in New York City. In 1917, she claimed that more babies in the U.S. were dying than soldiers in World War I. She became an ardent advocate for children’s health rights and spoke about the damage poverty and ignorance was causing them, and is perhaps most famous for being the doctor who tracked down “Typhoid Mary.” In her memoirs, “Fighting for Life,” she reflected on the realization that preventative care was as powerful as new treatments and cures to many people, remarking, “the way to keep people from dying from disease, it struck me suddenly, was to keep them from falling ill. Healthy people don’t die. It sounds like a completely witless remark, but at that time it was a startling idea. Preventative medicine had hardly been born yet and had no promotion in public health work.”

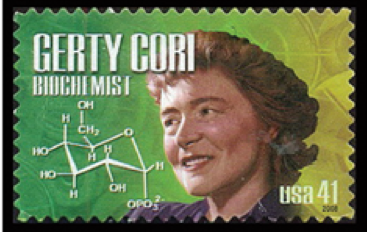

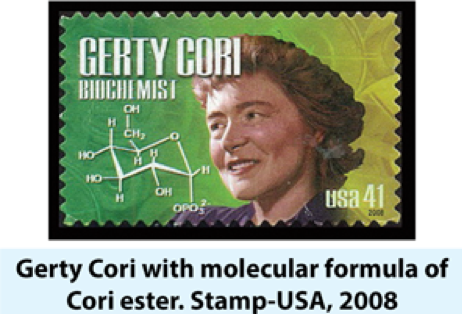

Another early twentieth century woman physician who deserves acknowledgement is Dr. Gerty Cori, who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology in 1896. She received her education in Germany and Prague, and immigrated to the US in 1922. In 1943, Dr. Cori was appointed an associate professor of Research Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology at Washington University School of Medicine. In 1947, she was promoted to professor and began studying carbohydrate metabolism. Conducting this research with her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, they discovered that when glycogen was broken down into glucose it formed a substance known as glucose-1-phosphatase, or a “Cori ester,” and identified the enzyme responsible for this process. Along with her husband, she received another Nobel Prize in 1947.

Another early twentieth century woman physician who deserves acknowledgement is Dr. Gerty Cori, who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology in 1896. She received her education in Germany and Prague, and immigrated to the US in 1922. In 1943, Dr. Cori was appointed an associate professor of Research Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology at Washington University School of Medicine. In 1947, she was promoted to professor and began studying carbohydrate metabolism. Conducting this research with her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, they discovered that when glycogen was broken down into glucose it formed a substance known as glucose-1-phosphatase, or a “Cori ester,” and identified the enzyme responsible for this process. Along with her husband, she received another Nobel Prize in 1947.

The female doctors of the 1940s made significant strides in the field of infant medicine. Every doctor and medical student in the U.S. today knows of Dr. Virginia Apgar, who taught hundreds of other doctors and revolutionized the field of perinatology by creating the Apgar Newborn Screening Score in 1949. This score is used all over the world during deliveries to evaluate the baby’s health and decide appropriate medical management – it has, no doubt, prevented thousands of infant deaths.

The female doctors of the 1940s made significant strides in the field of infant medicine. Every doctor and medical student in the U.S. today knows of Dr. Virginia Apgar, who taught hundreds of other doctors and revolutionized the field of perinatology by creating the Apgar Newborn Screening Score in 1949. This score is used all over the world during deliveries to evaluate the baby’s health and decide appropriate medical management – it has, no doubt, prevented thousands of infant deaths.

Dr. Helen Brooke Taussing was another champion for infants in this decade, who is known as the founder of pediatric cardiology and performed the first surgeries for infants with congenital cardiac defects. Dr. Taussing was also an investigator into limb defects in babies, and she documented the relationship between mothers taking thalidomide while pregnant and these defects. Along with Dr. Alfred Blalock, she also developed a surgical procedure to correct cyanosis in certain cardiac defects, called the Blalock-Taussing procedure. She received many awards, published hundreds of articles, and wrote a medical textbook: Congenital Malformations of the Heart. She became the first president of the American Heart Associated at the age of sixty-seven. It is amazing to note, in light of her many accomplishments, that Dr. Taussing suffered from dyslexia and was often thought to be mentally retarded as a child.

Dr. Helen Brooke Taussing was another champion for infants in this decade, who is known as the founder of pediatric cardiology and performed the first surgeries for infants with congenital cardiac defects. Dr. Taussing was also an investigator into limb defects in babies, and she documented the relationship between mothers taking thalidomide while pregnant and these defects. Along with Dr. Alfred Blalock, she also developed a surgical procedure to correct cyanosis in certain cardiac defects, called the Blalock-Taussing procedure. She received many awards, published hundreds of articles, and wrote a medical textbook: Congenital Malformations of the Heart. She became the first president of the American Heart Associated at the age of sixty-seven. It is amazing to note, in light of her many accomplishments, that Dr. Taussing suffered from dyslexia and was often thought to be mentally retarded as a child.

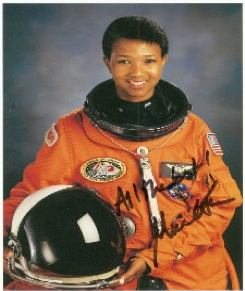

Another wave of great work was championed by women physicians during the 1980s. Dr. Mae Jemison graduated from medical school in 1981. After graduation, she worked as a peace corps medical officer in Liberia and Sierra Leone. When she returned to the US in 1985, she decided to follow a different dream by becoming the first Africa-American woman ever admitted into an astronaut training program. In 1992, with six other astronauts, she went into space on the Endeavor conducting weightlessness and motion sickness experiments.

Another wave of great work was championed by women physicians during the 1980s. Dr. Mae Jemison graduated from medical school in 1981. After graduation, she worked as a peace corps medical officer in Liberia and Sierra Leone. When she returned to the US in 1985, she decided to follow a different dream by becoming the first Africa-American woman ever admitted into an astronaut training program. In 1992, with six other astronauts, she went into space on the Endeavor conducting weightlessness and motion sickness experiments.

In 1986, Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston was working for the National Institute of Health (NIH) and published the results of a sickle cell disease study. This led to a nationwide screening program whereby newborns were tested to enable immediate treatment. Her conclusion – that sickle cell disease complications could be prevented if treated early – became a key policy of the U.S. Public Health Service and led to legislation to fund these nationwide screening programs. Dr. Gaston became the director of the US Bureau of Primary Health Care Health Resources and Services Administration in 1990, and was the first African-American woman to direct a major public health service bureau.

In 1986, Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston was working for the National Institute of Health (NIH) and published the results of a sickle cell disease study. This led to a nationwide screening program whereby newborns were tested to enable immediate treatment. Her conclusion – that sickle cell disease complications could be prevented if treated early – became a key policy of the U.S. Public Health Service and led to legislation to fund these nationwide screening programs. Dr. Gaston became the director of the US Bureau of Primary Health Care Health Resources and Services Administration in 1990, and was the first African-American woman to direct a major public health service bureau.

These are just a few examples of the remarkable contributions that physicians who are women have made to the field of medicine. Clearly all doctors, male and female alike, stand on the shoulders of these giants, as well as many others. Without the bravery of these women tearing down the gender boundaries, medicine would not be the same as it is today – their unique perspective shed light on life saving practices and discoveries, and they carved out a space for more women to become physicians in the future. They worked to let women be admitted to schools, to get clinical experience, to teach and manage and lead; now it is our turn to keep moving things forward. Where gender equality exists, the whole structure stands strong and succeeds any turmoil thrown at it. The work towards gender equality in medicine must continue – we owe it to doctors and patients of the past and future.

Promoting and Respecting Our Women Doctors (PROWD) is a group of women physician leaders from across the US who are committed to accelerating gender equity efforts. Follow their work @PROWDWomen

About the Author

Linda Girgis MD, FAAFP is a family physician practicing in South River, New Jersey and Clinical Assistant Professor at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. She was voted one of the top 5 healthcare bloggers in 2016. Follow her on twitter @DrLindaMD.