Overactive bladder (OAB) is a distressing bladder disorder marked by urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urge incontinence. It often has a negative impact on the quality of life, sleep, sexual function, and mental health.

OAB is marked by detrusor instability. Several models have been used to explain this but all are marked by increased connectivity and excitability of both detrusor smooth muscle as well as nerves. Growth factors appear to play a role in neural plasticity. Additionally, neurotransmitters, prostaglandins, and growth factors, such as nerve growth factor, allow for bidirectional communication between muscle/endothelium and nerve. In OAB, there appears to be some patchy denervation of the bladder, enlarged sensory neurons, hypertrophic ganglion cells, and an enhanced spinal micturition reflex. There also seems to be enhanced contractility of the smooth muscle of the bladder.

While the incidence of OAB is approximately equal in both men and women, symptoms tend to differ. In the EPIC study, one of the largest population based surveys, of more than 19,000 people over the age of 18 years in five different countries (Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK), approximately 11.6 % had OAB and the prevalence appeared similar in both men and women (10.8 % in men versus 12.8 % in women). Women tended to have more symptoms of storage (59.2 % versus 51.3 % in men) while men had more voiding symptoms (intermittency, slow stream, and straining) than women (25.7 % versus 19.5 %). In the US, it is estimated that 33 million Americans have OAB, or about 30% of men and 40 % of women. Experts suspect that the actual number is significantly higher, since many patients with OAB don’t seek help.

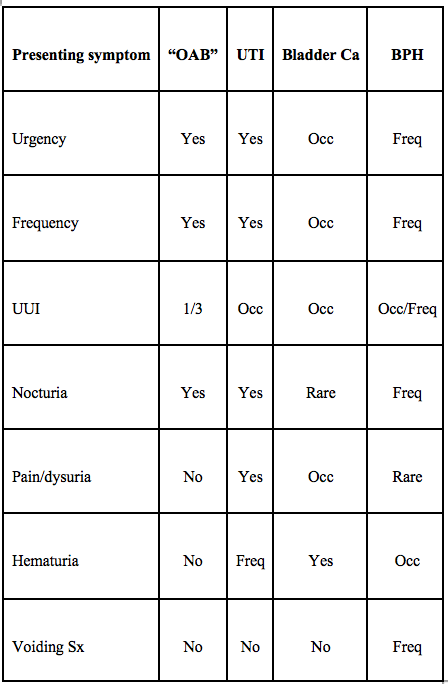

The symptoms of OAB can sometimes be confused with other urinary disorders. The following table from the Canadian Urological Association Journal provides a good guideline for distinguishing lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS):

OAB: overactive bladder; UTI: urinary tract infection; Ca: cancer; BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia; UUI: urge urinary incontinence; Occ: occasionally; Freq: frequently. Modified from Nitti 2003, AUA presentation. [1]

OAB can be more common when accompanying certain other conditions. Risk factors include increased age, neurologic disorders (including stroke, spinal cord injury, dementia, Parkinson’s Disease, and multiple sclerosis) diabetes mellitus, prostate enlargement, prior prostate surgeries, history of multiple pregnancies, prior pelvic surgery, radiotherapy to the pelvis, post-menopausal status, obesity, and race.

While the diagnosis of OAB is suggested by patient history, several tests may be useful. A urinalysis is done to evaluate for other causes such as urinary tract infections, diabetes, or underlying kidney problem. A post residual volume is also done to determine if the bladder fully empties and to measure any urine remaining in the bladder after voiding. Other tests that may be considered include ultrasound, bladder stress test, cystoscopy, urodynamic testing, and voiding cystourethrogram.

There are several different types of therapy that can be used for OAB. The first fall under behavioral interventions. Kegel exercises, or pelvic floor muscle exercises, are often the first-line therapy. Using these exercises, the pelvic floor as well as the urinary sphincter is strengthened. This in turn can help stop the involuntary bladder contractions. Other behavioral interventions include scheduled bathroom trips, bladder training, maintaining a healthy weight, and intermittent catheterization.

Several classes of medications can be used. The most commonly utilized are the anticholinergics, which act by blocking acetylcholine. This chemical is responsible for giving the message to the bladder to contract. These medications include: oxybutynin, tolerodine, trospium, darifenacin, solifenacin, and fesoterodine. Beta-3 adrenergic medications relaxes the smooth muscle in the walls of the bladder. This allows the bladder to hold more urine. The only medication in this class is mirabegron. Antispasmodic drugs reduce bladder spasms. Flavoxate is the only drug in this class. Some antidepressants have been used when other medications failed, however, none of them are FDA approved for this indication. In post-menopausal women, hormones such as topical estrogen may be used. It helps strengthen the muscles around the vagina, urethra, and bladder if they are weakened.

Botox is also an option for treatment, although studies show more benefit for those patients with neurogenic detrusor instability. While this option is now widely used, ongoing studies are being conducted about its use.

About the Author

Linda Girgis MD, FAAFP is a family physician practicing in South River, New Jersey. She was voted one of the top 5 healthcare bloggers in 2016. Follow her on twitter @DrLindaMD.